ABOUT US

Welcome to Native Blend Clothing, a proud Native American owned business rooted in Southwest Michigan.

We are dedicated to expressing the importance of mental health and embracing your true self. Our designs serve as reminders to keep pushing forward and remembering what you have already overcome at this point in your journey.

We have all felt alone; out of place.

Once hidden, but not anymore.

Show the world the real you.

We are ALL unique.

Together we can CONQUER life's challenges.

Welcome to our family; a tribe of MISFITS.

-

MISSION

At Native Blend Clothing, our mission is more than fashion; it’s about inspiring individuals to embrace their identity, encouraging self-pride, and advocating mental health awareness.

-

VISION

TO IGNITE REBELLIOUS SPIRITS AND EMPOWER INDIVIDUALS TO EMBRACE THEIR UNIQUENESS WITH BOLD, EXPRESSIVE FASHION THAT CHALLENGES CONVENTIONS, INSPIRES CONFIDENCE, AND SPARKS A MOVEMENT OF FEARLESS SELF EXPRESSION WORLDWIDE.

-

VALUES

-

Courage: Embrace challenges with bravery and resilience, facing obstacles head-on to achieve our goals.

Optimism: Maintain a positive mindset, believing in the potential for success and growth even in difficult times.

Nurturing: Promote a supportive and encouraging environment, growing the talents and personal development of our team members.

Quality: Always committed to delivering excellence in everything we do, striving for the highest standards of quality and customer relationships.

Unity: We value collaboration and teamwork, understanding that together, we can achieve more and overcome any challenges.

Empowerment: Empowering individuals to reach their full potential, providing opportunities for growth and advancement.

Resilience: We bounce back from setbacks stronger than before, learning from failures and using them as stepping stones to success.

-

Collapsible content

OUR STORY

Coming soon

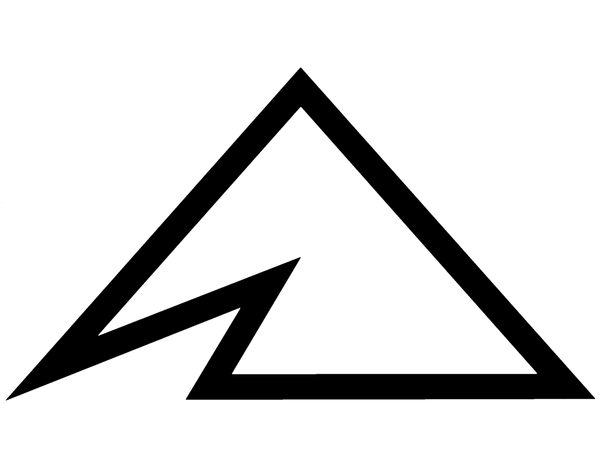

OUR LOGO

In a remote corner of the vast native wilderness, there lived a man named Brave Eagle. He was known for his courage, resilience, and deep connection to the land and its spirits.

One day, Brave Eagle heard of a legendary mountain that was said to be impossible to climb, a towering peak that challenged even the bravest souls.

Driven by a desire to prove his strength and conquer his own doubts, Brave Eagle embarked on a perilous journey to reach the summit of the impossible mountain. Along the way, he faced fierce storms, treacherous cliffs, and daunting obstacles that tested his physical and mental endurance.

As he climbed higher, Brave Eagle found himself fighting inner demons—fears, insecurities, and past traumas that threatened to hold him back. Doubt crept into his mind, whispering that the mountain was too high, too steep, too impossible to conquer.

Brave Eagle refused to give in to despair. Drawing strength from the teachings of his ancestors and the spirits of the land, he pressed on with determination and resilience. With each step, he recited prayers, sang ancient chants, and focused his mind on the goal ahead.

As the summit came into view, Brave Eagle felt a surge of emotion, a mixture of exhaustion, triumph, and awe. He realized that the true challenge had not been the mountain itself, but the internal struggles he had faced along the way.

At the summit, surrounded by the vast stretch of the wilderness, Brave Eagle felt a profound sense of peace and clarity wash over him. He understood that the impossible mountain had been a metaphor for his own journey, a testament to the power of perseverance, courage, and belief in oneself.

Descending from the summit, Brave Eagle returned to his tribe as a changed man. He shared his story, inspiring others to confront their own internal struggles and mental health battles with courage and willpower.

The moral of Brave Eagle's journey was clear: no mountain is truly impossible to climb when you have the strength and determination to overcome your own limitations.

Our logo represents the impossible mountain and the person wearing it possesses the strength to conquer it.

THE MISFIT TRIBE

The Misfit Tribe is a community of individuals who have all felt out of place or the need to be someone else in order to “fit in”. We share a common goal of self-improvement and mental health enhancement while embracing our uniqueness and differences, viewing them as strengths rather than weaknesses.

The Misfit Tribe is a beacon of acceptance, resilience, and growth, inspiring others to embrace their journey towards well-being and personal development.

Proudly repping your Misfit Tribe gear let’s others know; they are not alone.

BATTLE WORN COLLECTION

Our "Battle Worn" collection is a unique style that draws inspiration from the internal struggles and battles we face throughout our lives. This line of clothing not only shows earned battle scars, but the endurance and strength it takes to CONQUER YOURSELF.

The design elements of our "Battle Worn" clothing incorporate cut, torn, and uniquely dyed/faded garments, reflecting the wear and tear that comes from facing mental health battles. The garments also feature symbolic designs, representing inner turmoil, or empowering slogans that emphasize resilience and triumph over hardships.

This clothing line goes beyond fashion; it serves as a reminder of the courage and grit it takes to confront and conquer one's inner demons. By wearing these clothes, you can express solidarity with others facing similar challenges while also embracing your own battles and celebrating your strength in facing adversity.

NATIVE HERITAGE

POKAGON BAND OF POTAWATOMI INDIANS

Each Indigenous nation has its own creation story. Some stories tell that the Potawatomi have always been here. Other stories tell of migration from the Eastern seaboard with the Ojibwe and Odawa Nations. The three tribes loosely organized as the Three Fires Confederacy, with each serving an important role. The Ojibwe were said to be the Keepers of Tradition. The Odawa were known as the Keepers of the Trade. The Potawatomi were known as the Keepers of the Fire. Later, the Potawatomi migrated from north of Lakes Huron and Superior to the shores of the mshigmé or Great Lake. This location—in what is now Wisconsin, southern Michigan, northern Indiana, and northern Illinois—is where European explorers in the early 17th century first came upon the Potawatomi; they called themselves Neshnabék, meaning the original or true people.

As the United States frontier border moved west, boundary arguments and land cessions became a way of life for Native Americans. In 1830, the U.S. Congress passed the Indian Removal Act and directed that all American Indians be relocated to lands west of the Mississippi River, leaving the Great Lakes region open to further non-Indian development.

The 1833 Treaty of Chicago established the conditions for the removal of the Potawatomi from the Great Lakes area. When Michigan became a state in 1837, more pressure was put on the Potawatomi to move west. The hazardous trip killed one out of every ten people of the approximately 500 Potawatomi involved. As news of the terrible trip spread, some bands, consisting of small groups of families, fled to northern Michigan and Canada. Some also tried to hide in the forests and swamps of southwestern Michigan. The U.S. government sent soldiers to round up the Potawatomi they could find and move them at gunpoint to reservations in the west. This forced removal is now called the Potawatomi Trail of Death, similar to the more familiar Cherokee Trail of Tears.

However, a small group of Neshnabék, with Leopold Pokagon as one of their leaders, earned the right to remain in their homeland, in part because they had demonstrated a strong attachment to Catholicism. It is the descendants of this small group who constitute the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians.

When the American immigrants first came to southwestern Michigan in the early 19th century, they would have found Leopold Pokagon and his village in what is now Bertrand Township in Niles, Michigan. In 1838, Leopold and a small group from the St. Joseph Valley visited the Odawa at L’Arbre Croche to attempt to find a place to settle, for while the Treaty of 1833 allowed them to remain in Michigan, they were supposed to remove to the L’Arbre Croche area with the Odawa within five years. In 1836 the Treaty of Washington was struck between the Odawa and Ojibwe and ceded much of the lands in the north. Essentially, Leopold and his group were told there would be no room for them to move there. Upon returning to southwest Michigan, Leopold purchased land in Silver Creek Township using annuity monies accrued through several previous treaty negotiations, including the Treaty of 1833. It was in this time that Pokagon and several other groups moved collectively to Silver Creek Township, near present day Dowagiac, Michigan. Not long after, Brigadier General Hugh Brady threatened to force Pokagon’s Band out of Michigan. Pokagon, who by then was an old man in failing health, traveled to Detroit to get a written judgment from Epaphroditus Ransom of the Michigan Supreme Court to remain on their land.

Nearly one hundred years later, during the Great Depression, the federal government passed the Wheeler-Howard Act, also known as the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, which would provide tribes with resources to reestablish tribal governments. Although the Pokagon Band applied for recognition, the Bureau of Indian Affairs had limited funding and personnel to fully implement the Act, so decided to recognize only one Indian tribe in the lower peninsula of Michigan (the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe). It wasn’t until September 21, 1994 that the federally-recognized status of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi was reaffirmed by an act of Congress. After decades of effort by hundreds of Pokagon Band citizens and other volunteers, the Pokagon Band’s sovereignty was restored on that day in a signing ceremony at the White House with President Bill Clinton. This day is now celebrated as Sovereignty Day by citizens of the Pokagon Band. This Act did not mean that the Pokagon Band suddenly became an Indian tribe, rather that the federal government reaffirmed what the Pokagon Band had always known — they were a tribe.